This is the second post in the live-blogging Economics as Religion series. The first post was published on Monday, March 11.

“To the extent that any system of economic ideas offers an alternative vision of the ‘ultimate values,’ or ‘ultimate reality,’ that actually shapes the workings of history, economics is offering yet another grand prophecy in the biblical tradition.”

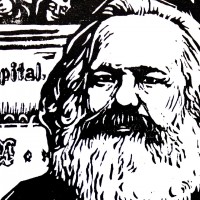

Karl Marx is well-known as an outspoken opponent of religious belief. Calling religion the “opiate” of the masses, he was convinced that religion suppressed the proletariat’s desire to improve their economic condition in favor of a more heavenly focus. But Marxist philosophy illustrates perfectly the power of underlying religious influences on economic thinking.

According to Nelson, Marx’s ideas are founded upon a biblical eschatology.

“Humankind has fallen into evil ways, corrupted by the workings of the forces of the class struggle. The resulting “alienation” for Marx has virtually the same meaning for the human situation as “original sin” in the biblical message…The prospect for escape from this terrible condition, however, is close at hand. God (now replaced in Marx by the economic laws of history) has promised to deliver the world from sin (alienation). There will be a fierce struggle and a great cataclysm (a final war in history between the capitalist and the working classes), followed by the arrival of the kingdom of God on earth (the triumph of the proletariat and the arrival of pure communism).

Marx, then, should be understood as considering himself a messiah. Though his value system is not made explicit and is decidedly anti-Christian, his philosophy is nothing if not religious. He offers a vision of “ultimate reality” that is to be brought about by economic forces alone.

His faith in economic forces is made manifest in his attributing the religious, social and cultural features of society to economic causes. Capitalists, Marx argues, manipulate social institutions in order to serve their ends, regardless of the stated ends of these institutions’ originators. The laws of economics have literally assumed the role of God, who orders and designs the universe and transcends human action.

Though Marxism itself did not find staying power across Western universities, its use of economics as a means to explain almost all social phenomena became a common feature of new economic theories — “economic gospels.” While Nelson does not explore the relation of this type of thinking to the advent of Darwinism (and, on that note, similar tendencies in other disciplines like psychology, sociology and history), the influence of natural selection and evolutionary biology likely had much to do with the advent of Marxist-like theories about economic history as tending toward one particular utopic end state.

“In the economic gospels, the existence of evil behavior in the world has reflected the severity of the competition for physical survival of the past.”

Instead of viewing economic prosperity as the result of sound moral foundations, the economic gospel views material deprivation as the cause of bad morals. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, according to one authority, believed “it was property alone which induced crime and wars,” corrupting the happy state of nature by conflicts over material possession. In like manner, Friedrich Engels writes that the new rate of industrial production in the communist utopia will satisfy all demand, thereby rendering conflicts over material possessions a thing of the past.

While the economic gospel might have begun with Marx, it was most prominently displayed in the work of John Maynard Keynes. In his essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” Keynes writes that capitalism is a “disgusting” system that separates human beings from their inner, better selves. But an era of abundance is coming whereby these problems will be eradicated and cut-throat capitalism will become unnecessary, giving way instead to an era of abundance and peace. All that is needed is faith and trust in economists’ incremental adjustments to the current economic system.

While presented as economic theory, Keynes’ ideas were nothing short of a new secular theology. Its followers were fueled by the passionate fervor characteristic of religious belief. As Joseph Schumpeter writes,

“A Keynesian school formed itself, not a school in that loose sense in which some historians of economics speak of a French, German, Italian school, but a genuine one which is a sociological entity, namely, a group that professes allegiance to One Master and One Doctrine, and has its inner circle, its propagandists, its watchwords, its esoteric and its popular doctrine.”

Keynes’ doctrines also had a special advantage over the likes of Marxism, in that his was carefully woven into the fabric of popular opinion. By recommending incremental change funneled through the medium of democratic government, Keynes avoided the cultish aura of Marx, and his theories soon become instantiated as quasi-law among economists and politicians alike. Fortunately for him, few saw his ideas for what they really were: tenets of a new, secular, economic faith.

No comments yet.